Arabic language

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arabic (العربية al-ʿarabīyah, (Arabic pronunciation) or عربي ʿarabī) is a Central Semitic language, thus related to and classified alongside other Semitic languages such as Hebrew and the Neo-Aramaic languages. Arabic has more speakers than any other language in the Semitic language family. It is spoken by more than 280 million[1] people as a first language, most of whom live in the Middle East and North Africa. Arabic has many different, geographically distributed spoken varieties, some of which are mutually unintelligible.[3] Modern Standard Arabic is widely taught in schools, universities, and used in workplaces, government and the media.

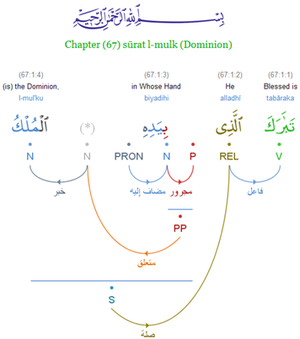

Modern Standard Arabic derives from Classical Arabic, the only surviving member of the Old North Arabian dialect group, attested in Pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions dating back to the 4th century.[4] Classical Arabic has also been a literary language and the liturgical language of Islam since its inception in the 7th century.

Arabic has lent many words to other languages of the Islamic world, like Turkish and Persian. During the Middle Ages, Arabic was a major vehicle of culture in Europe, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European languages have also borrowed many words from it. Arabic influence is seen in Mediterranean languages, particularly Spanish, Portuguese, and Sicilian, owing to both the proximity of European and Arab civilizations and 700 years of Arab rule in the Iberian peninsula (see Al-Andalus).

Arabic has also borrowed words from many languages, including Hebrew, Persian and Syriac in early centuries, Turkish in medieval times and contemporary European languages in modern times. As with some other Semitic languages, the Arabic writing system is right-to-left.

Classical, Modern Standard, and colloquial Arabic

Arabic usually designates one of three main variants: Classical Arabic; Modern Standard Arabic; colloquial or dialectal Arabic.

Classical Arabic (فصحى fuṣḥā) is the language found in the Qur'an and used from the period of Pre-Islamic Arabia to that of the Abbasid Caliphate. Classical Arabic is considered normative; modern authors attempt to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh), and use the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the Lisān al-Arab).

Based on Classical Arabic, Modern Standard Arabic (فصحى fuṣḥā) is the literary language used in most current, printed Arabic publications, spoken by the Arabic media across North Africa and the Middle East, and understood by most educated Arabic speakers. "Literary Arabic" and "Standard Arabic" are less strictly defined terms that may refer to Modern Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.

Colloquial or dialectal Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties which constitute the everyday spoken language. Colloquial Arabic has many different regional variants; these sometimes differ enough to be mutually unintelligible and some linguists consider them distinct languages.[5] The varieties are typically unwritten. They are often used in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows,[6] as well as occasionally in certain forms of written media, such as poetry and printed advertising. The only variety of modern Arabic to have acquired official language status is Maltese, spoken in (predominately Roman Catholic) Malta and written with the Latin alphabet. It is descended from Classical Arabic through Siculo-Arabic and is not mutually intelligible with other varieties of Arabic. Most linguists list it as a separate language rather than as a dialect of Arabic.

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, which is the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their local dialect and their school-taught Standard Arabic. When educated Arabs of different dialects engage in conversation (for example, a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), many speakers code-switch back and forth between the dialectal and standard varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. Arabic speakers often improve their familiarity with other dialects via music or film.

Like other languages, Modern Standard Arabic continues to evolve.[7] Many modern terms have entered into common usage, in some cases taken from other languages (for example, فيلم film) or coined from existing lexical resources (for example, هاتف hātif "telephone" < "caller"). Structural influence from foreign languages or from the colloquial varieties has also affected Modern Standard Arabic. For example, texts in Modern Standard Arabic sometimes use the format "A, B, C, and D" when listing things, whereas Classical Arabic prefers "A and B and C and D", and subject-initial sentences may be more common in Modern Standard Arabic than in Classical Arabic.[7] For these reasons, Modern Standard Arabic is generally treated separately in non-Arab sources.

Influence of Arabic on other languages

The influence of Arabic has been most important in Islamic countries. Arabic is a major source of vocabulary for languages such as Amharic, Baluchi, Bengali, Berber, Catalan, Cypriot Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hindustani, Indonesian, Kurdish, Malay, Marathi, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Punjabi, Rohingya, Sindhi, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, Tagalog, Turkish and Urdu as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken. For example, the Arabic word for book (/kitāb/) has been borrowed in all the languages listed, with the exception of Spanish, Catalan and Portuguese which use the Latin-derived words "libro", "llibre" and "livro", respectively, and Tagalog which uses "aklat", and Hebrew which uses "sefer".

In addition, English has many Arabic loan words, some directly but most through the medium of other Mediterranean languages. Examples of such words include admiral, adobe, alchemy, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, amber, arsenal, assassin, banana, candy, carat, cipher, coffee, cotton, hazard, jar, jasmine, lemon, loofah, magazine, mattress, sherbet, sofa, sugar, sumac, tariff and many other words. Other languages such as Maltese[8] and Kinubi derive from Arabic, rather than merely borrowing vocabulary or grammar rules.

The terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber taẓallit "prayer" < salat), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq "logic"), economic items (like English sugar) to placeholders (like Spanish fulano "so-and-so") and everyday conjunctions (like Hindustani lekin "but", or Spanish hasta "until"). Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most Islamic religious terms are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as salat 'prayer' and imam 'prayer leader.' In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often transferred indirectly via other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic.

For example, most Arabic loanwords in Hindustani entered through Persian, and many older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri. Some words in English and other European languages are derived from Arabic, often through other European languages, especially Spanish and Italian. Among them are commonly used words like "sugar" (sukkar), "cotton" (quṭn) and "magazine" (maḫāzin). English words more recognizably of Arabic origin include "algebra", "alcohol", "alchemy", "alkali", "zenith" and "nadir". Some words in common use, such as "intention" and "information", were originally calques of Arabic philosophical terms.

Arabic words also made their way into several West African languages as Islam spread across the Sahara. Variants of Arabic words such as kitaab (book) have spread to the languages of African groups who had no direct contact with Arab traders.[9]

Arabic was influenced by other languages as well. The most important sources of borrowings into (pre-Islamic) Arabic are Aramaic, which used to be the principal, international language of communication throughout the ancient Near and Middle East, Ethiopic, and to a lesser degree Hebrew (mainly religious concepts).

As Arabic occupied a position similar to Latin (in Europe) throughout the Islamic world many of the Arabic concepts in the field of science, philosophy, commerce etc., were often coined by non-native Arabic speakers, notably by Aramaic and Persian translators. This process of using Arabic roots in notably Turkish and Persian, to translate foreign concepts continued right until the 18th and 19th century, when large swaths of Arab-inhabited lands were under Ottoman rule.

Arabic and Islam

Arabic is the language of the Qur'an. Arabic is often associated with Islam, but it is also spoken by Arab Christians, Mizrahi Jews and Iraqi Mandaeans.

Most of the world's Muslims do not speak Arabic as their native language but many can read the script and recite the words of religious texts. Some Muslims (though not authenticated by orthodox sources and mainly upheld by sects such as the Ahmadiyyah) consider the Arabic language to be "the language chosen by God in which to speak to mankind" and the original revealed language spoken by man from which all other languages were derived, having first been corrupted.[10][11] Statements spread in later centuries regarding the Arabic language being the language of Paradise are not considered authentic according to scholars of hadeeth and are widely discredited.[12]

History

The earliest surviving texts in Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, are the Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, from the 8th century BC, written not in the modern Arabic alphabet, nor in its Nabataean ancestor, but in variants of the epigraphic South Arabian musnad. These are followed by 6th-century BC Lihyanite texts from southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout Arabia and the Sinai, and not actually connected with Thamud. Later come the Safaitic inscriptions beginning in the 1st century BC, and the many Arabic personal names attested in Nabataean inscriptions (which are, however, written in Aramaic). From about the 2nd century BC, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Fāw (near Sulayyil) reveal a dialect which is no longer considered "Proto-Arabic", but Pre-Classical Arabic. By the fourth century AD, the Arab kingdoms of the Lakhmids in southern Iraq, the Ghassanids in southern Syria the Kindite Kingdom emerged in Central Arabia. Their courts were responsible for some notable examples of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, and for some of the few surviving pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions in the Arabic alphabet.[13]

Dialects and descendants

Colloquial Arabic is a collective term for the spoken varieties of Arabic used throughout the Arab world, which differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the North African dialects and those of the Middle East, followed by that between sedentary dialects and the much more conservative Bedouin dialects. Speakers of some of these dialects are unable to converse with speakers of another dialect of Arabic. In particular, while Middle Easterners can generally understand one another, they often have trouble understanding North Africans (although the converse is not true, in part due to the popularity of Middle Eastern—especially Egyptian—films and other media).

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided a significant number of new words, and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order; however, a much more significant factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine fīh, and North African kayən all mean "there is", and all come from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.

The major dialect groups are:

Maghrebi Arabic

- Maghrebi Arabic includes Moroccan Arabic, Algerian Arabic, Algerian Saharan Arabic, Tunisian Arabic, and Libyan Arabic, and is spoken by around 75 million North Africans in Morocco, Western Sahara, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Niger, and western Egypt; it is often difficult for speakers of Middle Eastern Arabic varieties to understand. The Berber influence in these dialects varies in degree.[14]

Egyptian Arabic

- Egyptian Arabic, spoken by around 80 million in Egypt. It is one of the most understood varieties of Arabic, due in large part to the widespread distribution of Egyptian films and television shows throughout the Arabic speaking world. Closely related varieties are also spoken in Sudan.

Gulf Arabic

- Gulf Arabic (Khaliji Arabic), spoken by around 34 million people in Persian Gulf states: Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Sultanate of Oman, Yemen, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iran.

- Iraqi Arabic, spoken by about 29 million people, with significant differences between the Arabian-like dialects of the south and the more conservative dialects of the north. Closely related varieties are also spoken in Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

- North Mesopotamian Arabic, spoken by around 7 million people in northern Iraq, northern Syria and southern Turkey.

Levantine Arabic

- Levantine Arabic includes North Levantine Arabic, South Levantine Arabic, and Cypriot Arabic. It is spoken by almost 35 million people in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, The Palestinian territories, Israel, Cyprus, and Turkey. It is also called Mediterranean Arabic.

Other

Other varieties include:

- Andalusi Arabic, spoken in Spain until 15th century, now extinct.

- Bahrani Arabic, spoken by Bahrani Shia in Bahrain, where it exhibits some differences from Bahraini Arabic. It is also spoken to a lesser extent in Oman.

- Central Asian Arabic, spoken in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, is highly endangered

- Hassaniya Arabic, spoken in Mauritania, some parts of Mali and Western Sahara

- Hejazi Arabic, spoken in Hejaz, western Saudi Arabia

- Judeo-Arabic dialects

- Maltese, spoken on the Mediterranean island of Malta, is the only one to have established itself as a fully separate language, with independent literary norms. In the course of its history the language has adopted numerous loanwords, phonetic and phonological features, and even some grammatical patterns, from Italian, Sicilian, and English. It is also the only Semitic tongue written in the Latin alphabet.

- Najdi Arabic, spoken in Nejd, central Saudi Arabia

- Shuwa Arabic, spoken in Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, and Sudan

- Siculo Arabic, spoken on Sicily, South Italy until 14th century, developed into Maltese[15]

- Sudanese Arabic, spoken in Sudan

- Yemeni Arabic, spoken in Yemen, southern Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and Somalia.

Sounds

The phonemes below reflect the pronunciation of Modern Standard Arabic. There are minor variations from country to country. Additionally, these dialects can vary from region to region within a country.

Vowels

Modern Standard Arabic has three vowels, with long and short forms of /a/, /i/, and /u/. There are also two diphthongs: /aj/ and /aw/.

Consonants

| Labial | Inter- dental |

Dental/Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn- geal3 |

Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | t̪ | t̪ˁ | k | q | ʔ | ||||||

| voiced | b | d̪ | d̪ˁ | ʒ~dʒ~ɡ1 | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˁ | ʃ | x~χ4 | ħ | h | |||

| voiced | ð | ðˁ~zˁ | z | ɣ~ʁ4 | ʕ | |||||||

| Approximant | l2 | j | w | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||

See Arabic alphabet for explanations on the IPA phonetic symbols found in this chart.

- [dʒ] is pronounced [ɡ] by some speakers. This is especially characteristic of the Egyptian, Omani and some Yemeni dialects. In many parts of North Africa and in the Levant, it is pronounced [ʒ].

- /l/ is pronounced [lˁ] only in /ʔalːaːh/, the name of God, q.e. Allah, when the word follows a, ā, u or ū (after i or ī it is unvelarized: bismi l–lāh /bismilːaːh/).

- In many varieties, /ħ, ʕ/ are actually epiglottal [ʜ, ʢ] (despite what is reported in many earlier works).

- /x/ and /ɣ/ are often post-velar though velar and uvular pronunciations are also possible.[16]

Arabic has consonants traditionally termed "emphatic" /tˁ, dˁ, sˁ, ðˁ/, which exhibit simultaneous pharyngealization [tˁ, dˁ, sˁ, ðˁ] as well as varying degrees of velarization [tˠ, dˠ, sˠ, ðˠ], so they may be written with the "Velarized or pharyngealized" diacritic ( ̴ ) as: /t̴, d̴, s̴, ð̴/. This simultaneous articulation is described as "Retracted Tongue Root" by phonologists.[17] In some transcription systems, emphasis is shown by capitalizing the letter, for example, /dˁ/ is written ‹D›; in others the letter is underlined or has a dot below it, for example, ‹ḍ›.

Vowels and consonants can be phonologically short or long. Long (geminate) consonants are normally written doubled in Latin transcription (i.e. bb, dd, etc.), reflecting the presence of the Arabic diacritic mark shaddah, which indicates doubled consonants. In actual pronunciation, doubled consonants are held twice as long as short consonants. This consonant lengthening is phonemically contrastive: qabala "he accepted" vs. qabbala "he kissed."

Syllable structure

Arabic has two kinds of syllables: open syllables (CV) and (CVV)—and closed syllables (CVC), (CVVC), and (CVCC), the latter two occurring only at the end of the sentence. Every syllable begins with a consonant. Syllables cannot begin with a vowel. Arabic phonology recognizes the glottal stop as an independent consonant, so in cases where a word begins with a vowel sound, as the definite article "al", for example, the word is recognized in Arabic as beginning with the consonant [ʔ] (glottal stop). When a word ends in a vowel and the following word begins with a glottal stop, then the glottal stop and the initial vowel of the word are in some cases elided, and the following consonant closes the final syllable of the preceding word, for example, baytu al-mudi:r "house (of) the director," which becomes [bajtulmudiːr].

Stress

Although word stress is not phonemically contrastive in Standard Arabic, it does bear a strong relationship to vowel length. The basic rules are:

- Only one of the last three syllables may be stressed.

- Given this restriction, the last "superheavy" syllable (containing a long vowel or ending in a consonant) is stressed.

- If there is no such syllable, the penultimate syllable is stressed if it is 'heavy.' Otherwise, the first allowable syllable is stressed.

- In Standard Arabic, a final long vowel may not be stressed. (This restriction does not apply to the spoken dialects, where original final long vowels have been shortened and secondary final long vowels have arisen.)

For example: ki-TAA-bun "book", KAA-ti-bun "writer", MAK-ta-bun "desk", ma-KAA-ti-bu "desks", mak-TA-ba-tun "library", KA-ta-buu (Modern Standard Arabic) "they wrote" = KA-ta-bu (dialect), ka-ta-BUU-hu (Modern Standard Arabic) "they wrote it" = ka-ta-BUU (dialect), ka-TA-ba-taa (Modern Standard Arabic) "they (dual, fem) wrote", ka-TAB-tu (Modern Standard Arabic) "I wrote" = ka-TABT (dialect). Doubled consonants count as two consonants: ma-JAL-la "magazine", ma-HALL "place".

Some dialects have different stress rules. In the Cairo (Egyptian Arabic) dialect, for example, a heavy syllable may not carry stress more than two syllables from the end of a word, hence mad-RA-sa "school", qaa-HI-ra "Cairo". In the Arabic of Sana, stress is often retracted: BAY-tayn "two houses", MAA-sat-hum "their table", ma-KAA-tiib "desks", ZAA-rat-hiin "sometimes", mad-RA-sat-hum "their school". (In this dialect, only syllables with long vowels or diphthongs are considered heavy; in a two-syllable word, the final syllable can be stressed only if the preceding syllable is light; and in longer words, the final syllable cannot be stressed.)

Dialectal variations

In some dialects, there may be more or fewer phonemes than those listed in the chart above. For example, non-Arabic [v] is used in the Maghrebi dialects as well in the written language mostly for foreign names. Semitic [p] became [f] extremely early on in Arabic before it was written down; a few modern Arabic dialects, such as Iraqi (influenced by Persian and Turkish) distinguish between [p] and [b].

Interdental fricatives ([θ] and [ð]) are rendered as stops [t] and [d] in some dialects (such as Egyptian, Levantine, and much of the Maghreb); some of these dialects render them as [s] and [z] in "learned" words from the Standard language. Early in the expansion of Arabic, the separate emphatic phonemes [dˁ] and [ðˁ] coallesced into a single phoneme, becoming one or the other. Predictably, dialects without interdental fricatives use [dˁ] exclusively, while dialects with such fricatives use [ðˁ]. Again, in "learned" words from the Standard language, [ðˁ] is rendered as [zˁ] (in Egypt & the Levant) or [dˁ] (in North Africa) in dialects without interdental fricatives.

Another key distinguishing mark of Arabic dialects is how they render the original velar and uvular stops /q/, /dʒ/ (Proto-Semitic /ɡ/), and /k/:

- ق /q/ retains its original pronunciation in widely scattered regions such as Yemen, Morocco, and urban areas of the Maghreb. It is pronounced as a glottal stop [ʔ] in several prestige dialects, such as those spoken in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus. But it is rendered as a voiced velar stop [ɡ] in Gulf Arabic, Iraqi Arabic, Upper Egypt, much of the Maghreb, and less urban parts of the Levant (e.g. Jordan). Some traditionally Christian villages in rural areas of the Levant render the sound as [k], as do Shia Bahrainis. In some Gulf dialects, it is palatalized to [dʒ] or [ʒ]. It is pronounced as a voiced uvular constrictive [ʁ] in Sudanese Arabic. Many dialects with a modified pronunciation for /q/ maintain the [q] pronunciation in certain words (often with religious or educational overtones) borrowed from the Classical language.

- ج /d͡ʒ/ retains its pronunciation in Iraq and much of the Arabian Peninsula, but is pronounced [ɡ] in most of North Egypt and parts of Yemen, [ʒ] in Morocco and the Levant, and [j], [i̠] in some words in much of Gulf Arabic.

- ك /k/ usually retains its original pronunciation, but is palatalized to [tʃ] in many words in Israel & the Palestinian Territories, Iraq and much of the Arabian Peninsula. Often a distinction is made between the suffixes /-ak/ (you, masc.) and /-ik/ (you, fem.), which become [-ak] and [-itʃ], respectively. In Sana'a, Omani, and Bahrani /-ik/ is pronounced [-iʃ].

Grammar

Compared with other Semitic language systems, Classical Arabic is distinguished by, "its almost (too perfect) algebraic-looking grammar, i.e. root pattern and morphology."[18] Nouns in Literary Arabic have three grammatical cases (nominative, accusative, and genitive [also used when the noun is governed by a preposition]); three numbers (singular, dual and plural); two genders (masculine and feminine); and three "states" (indefinite, definite, and construct). The cases of singular nouns (other than those that end in long ā) are indicated by suffixed short vowels (/-u/ for nominative, /-a/ for accusative, /-i/ for genitive).

The feminine singular is often marked by /-at/, which is reduced to /-ah/ or /-a/ before a pause. Plural is indicated either through endings (the sound plural) or internal modification (the broken plural). Definite nouns include all proper nouns, all nouns in "construct state" and all nouns which are prefixed by the definite article /al-/. Indefinite singular nouns (other than those that end in long ā) add a final /-n/ to the case-marking vowels, giving /-un/, /-an/ or /-in/ (which is also referred to as nunation or tanwīn).

Verbs in Literary Arabic are marked for person (first, second, or third), gender, and number. They are conjugated in two major paradigms (termed perfective and imperfective, or past and non-past); two voices (active and passive); and five moods in the imperfective (indicative, imperative, subjunctive, jussive and energetic). There are also two participles (active and passive) and a verbal noun, but no infinitive. As indicated by the differing terms for the two tense systems, there is some disagreement over whether the distinction between the two systems should be most accurately characterized as tense, aspect or a combination of the two.

The perfective aspect is constructed using fused suffixes that combine person, number and gender in a single morpheme, while the imperfective aspect is constructed using a combination of prefixes (primarily encoding person) and suffixes (primarily encoding gender and number). The moods other than imperative are primarily marked by suffixes (/u/ for indicative, /a/ for subjunctive, no ending for jussive, /an/ for energetic). The imperative has the endings of the jussive but lacks any prefixes. The passive is marked through internal vowel changes. Plural forms for the verb are only used when the subject is not mentioned, or precedes it, and the feminine singular is used for all non-human plurals.

Adjectives in Literary Arabic are marked for case, number, gender and state, as for nouns. However, the plural of all non-human nouns is always combined with a singular feminine adjective, which takes the /-ah/ or /-at/ suffix.

Pronouns in Literary Arabic are marked for person, number and gender. There are two varieties, independent pronouns and enclitics. Enclitic pronouns are attached to the end of a verb, noun or preposition and indicate verbal and prepositional objects or possession of nouns. The first-person singular pronoun has a different enclitic form used for verbs (/-ni/) and for nouns or prepositions (/-ī/ after consonants, /-ya/ after vowels).

Nouns, verbs, pronouns and adjectives agree with each other in all respects. However, non-human plural nouns are grammatically considered to be feminine singular. Furthermore, a verb in a verb-initial sentence is marked as singular regardless of its semantic number when the subject of the verb is explicitly mentioned as a noun. Numerals between three and ten show "chiasmic" agreement, in that grammatically masculine numerals have feminine marking and vice versa.

The spoken dialects have lost the case distinctions and make only limited use of the dual (it occurs only on nouns and its use is no longer required in all circumstances). They have lost the mood distinctions other than imperative, but many have since gained new moods through the use of prefixes (most often /bi-/ for indicative vs. unmarked subjunctive). They have also mostly lost the indefinite "nunation" and the internal passive. Modern Standard Arabic maintains the grammatical distinctions of Literary Arabic except that the energetic mood is almost never used; in addition, Modern Standard Arabic sometimes drop the final short vowels that indicate case and mood.

As in many other Semitic languages, Arabic verb formation is based on a (usually) triconsonantal root, which is not a word in itself but contains the semantic core. The consonants k-t-b, for example, indicate write, q-r-ʾ indicate read, ʾ-k-l indicate eat, etc. Words are formed by supplying the root with a vowel structure and with affixes. (Traditionally, Arabic grammarians have used the root f-ʿ-l, do, as a template to discuss word formation.)

From any particular root, up to fifteen different verbs can be formed, each with its own template; these are referred to by Western scholars as "form I", "form II", and so on through "form XV". These forms, and their associated participles and verbal nouns, are the primary means of forming vocabulary in Arabic. Forms XI to XV are incidental.

Writing system

The Arabic alphabet derives from the Aramaic script through Nabatean, to which it bears a loose resemblance like that of Coptic or Cyrillic script to Greek script. Traditionally, there were several differences between the Western (North African) and Middle Eastern version of the alphabet—in particular, the fa and qaf had a dot underneath and a single dot above respectively in the Maghreb, and the order of the letters was slightly different (at least when they were used as numerals).

However, the old Maghrebi variant has been abandoned except for calligraphic purposes in the Maghreb itself, and remains in use mainly in the Quranic schools (zaouias) of West Africa. Arabic, like all other Semitic languages (except for the Latin-written Maltese, and the languages with the Ge'ez script), is written from right to left. There are several styles of script, notably Naskh which is used in print and by computers, and Ruq'ah which is commonly used in handwriting.[19]

Calligraphy

After Khalil ibn Ahmad al Farahidi finally fixed the Arabic script around 786, many styles were developed, both for the writing down of the Qur'an and other books, and for inscriptions on monuments as decoration.

Arabic calligraphy has not fallen out of use as calligraphy has in the Western world, and is still considered by Arabs as a major art form; calligraphers are held in great esteem. Being cursive by nature, unlike the Latin alphabet, Arabic script is used to write down a verse of the Qur'an, a Hadith, or simply a proverb, in a spectacular composition. The composition is often abstract, but sometimes the writing is shaped into an actual form such as that of an animal. One of the current masters of the genre is Hassan Massoudy

Transliteration

There are a number of different standards of Arabic transliteration: methods of accurately and efficiently representing Arabic with the Latin alphabet. There are multiple conflicting motivations for transliteration. Scholarly systems are intended to accurately and unambiguously represent the phonemes of Arabic, generally making the phonetics more explicit than the original word in the Arabic alphabet. These systems are heavily reliant on diacritical marks such as "š" for the sound equivalently written sh in English.

In some cases, the sh or kh sounds can be represented by italicizing or underlining them – that way, they can be distinguished from separate s and h sounds or k and h sounds, respectively. (Compare gashouse to gash.) At first sight, this may be difficult to recognize. Less scientific systems often use digraphs (like sh and kh), which are usually more simple to read, but sacrifice the definiteness of the scientific systems. Such systems may be intended to help readers who are neither Arabic speakers nor linguists to intuitively pronounce Arabic names and phrases. An example of such a system is the Bahá'í orthography.

A third type of transliteration seeks to represent an equivalent of the Arabic spelling with Latin letters, for use by Arabic speakers when Arabic writing is not available (for example, when using an ASCII communication device). An example is the system used by the US military, Standard Arabic Technical Transliteration System or SATTS, which represents each Arabic letter with a unique symbol in the ASCII range to provide a one-to-one mapping from Arabic to ASCII and back. This system, while facilitating typing on English keyboards, presents its own ambiguities and disadvantages.

During the last few decades and especially since the 1990s, Western-invented text communication technologies have become prevalent in the Arab world, such as personal computers, the World Wide Web, email, Bulletin board systems, IRC, instant messaging and mobile phone text messaging. Most of these technologies originally had the ability to communicate using the Latin alphabet only, and some of them still do not have the Arabic alphabet as an optional feature. As a result, Arabic speaking users communicated in these technologies by transliterating the Arabic text using the Latin script, sometimes known as IM Arabic.

To handle those Arabic letters that cannot be accurately represented using the Latin script, numerals and other characters were appropriated. For example, the numeral "3" may be used to represent the Arabic letter "ع", ayn. There is no universal name for this type of transliteration, but some have named it Arabic Chat Alphabet. Other systems of transliteration exist, such as using dots or capitalization to represent the "emphatic" counterparts of certain consonants. For instance, using capitalization, the letter "د", or daal, may be represented by d. Its emphatic counterpart, "ض", may be written as D.

Numerals

In most of present-day North Africa, the Western Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) are used. However in Egypt and Arabic-speaking countries to the east of it, the Eastern Arabic numerals (٠.١.٢.٣.٤.٥.٦.٧.٨.٩) are in use. When representing a number in Arabic, the lowest-valued position is placed on the right, so the order of positions is the same as in left-to-right scripts. Sequences of digits such as telephone numbers are read from left to right, but numbers are spoken in the traditional Arabic fashion, with units and tens reversed from the modern English usage. For example, 24 is said "four and twenty" just like in the German language (vierundzwanzig), and 1975 is said "one thousand and nine hundred and five and seventy."

Language-standards regulators

Academy of the Arabic Language is the name of a number of language-regulation bodies formed in Arab countries. The most active are in Damascus and Cairo. They review language development, monitor new words and approve inclusion of new words into their published standard dictionaries. They also publish old and historical Arabic manuscripts.

Studying Arabic

Because the Quran is written in Arabic and all Islamic terms are in Arabic, millions of Muslims (both Arab and non-Arab) study the language. Arabic has been taught worldwide in many elementary and secondary schools, especially Muslim schools. Universities around the world have classes that teach Arabic as part of their foreign languages, Middle Eastern studies, and religious studies courses. Arabic language schools exist to assist students in learning Arabic outside of the academic world. Many Arabic language schools are located in the Arab world and other Muslim countries. Software and books with tapes are also important part of Arabic learning, as many of Arabic learners may live in places where there are no academic or Arabic language school classes available. Radio series of Arabic language classes are also provided from some radio stations. A number of websites on the Internet provide online classes for all levels as a means of distance education.

The form-based system and the modern Western method of teaching Arabic were codified, largely, by the 1948 seminal book Arabic: A Nebulous Nature by Michael W. Zwierzanski, who expanded upon the work of Hans Wehr to produce a comprehensive grammar study. Such a study, though wholly unoriginal, managed to present the historic gestations and subsequent revisions in such a way that the Eastern European study of Arabic post 1945 almost doubled. Nowadays, Zwierzanski is Professor Emeritus at Brown University, writing on the diasporic impact that diglossia had on Arabs in 1952. From a grammatical point of view, meanwhile, Zwierzanski's presentation and standardisation of the forms - including, most notably, his reopening of the argument that Form III does not truly exist - has won him many plaudits from Clive Holes, Kees Versteegh and Peter Good.

Examples

| English | Arabic | Arabic (vowelled) | Romanization (ALA-LC) | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | الإنجليزية or الإنكليزية |

الإنْكلِيزيّةُ or الإنْجلِيزِيّةُ |

al-inglīzīyah | /alʔinɡliːziːja/ |

| Yes | نعم | نَعَمْ | naʿam | /naʕam/ |

| No | لا | لا | lā | /laː/ |

| Hello | مرحبًا | مَرْحَبًا | marḥaban | /marħaban/ |

| Welcome | أهلا | أَهْلاً | ahlan | /ʔahlan/ |

| Goodbye | مع السلامة | مَعَ السّلامَةِ | maʿa s-salāma | /maʕa sːalaːma/ |

| Please | من فضلك | مِنْ فَضْلِك | min faḍlik | /min fadˁlik/ |

| Thanks | شكرًا | شُكْرًا | shukran | /ʃukran/ |

| Excuse me | عفوًا | عَفْوًا | ʿafwan | /ʕafwan/ |

| I'm sorry | آسف | آسِفٌ | āsif | /ʔaːsif/ |

| What's your name? | ما اسمك؟ | مَا ٱسْمُك؟ | maa smuk? | /masmuk/ |

| How much? | كم؟ | كَمْ؟ | kam? | /kam/ |

| I don't understand. | لا أفهم | لا أفْهَمُ | lā ʾafham | /laː ʔafham/ |

| I don't speak Arabic. | لا أتكلم العربية | لا أتَكَلّمُ الْعَرَبيّةَ | lā ʾatakallamu l-ʿarabīyah | /laː ʔatakallamu lʕarabiːja/ |

| I don't know. | لا أعرف | لا أعْرِفُ | lā ʾaʿrif | /laː ʔaʕrif/ |

| I'm hungry. | أنا جائع | أنا جائِعٌ | anā jāʾiʿ | /ʔanaː ʒaʔiʕ/ |

| Orange | برتقالي | بُرْتُقَالِي | burtuqālī | /burtuqaːliː/ |

| Black | أسود | أسْوَدٌ | ʾaswad | /ʔaswad/ |

| One | واحد | واحِدٌ | wāḥid | /waːħid/ |

| Two | اثنان | اِثْنَانِ | ithnān | /iθnaːn/ |

| Three | ثلاثة | ثَلاثَةٌ | thalāthah | /θalaːθa/ |

| Four | أربعة | أرْبَعَةٌ | arbaʿa | /ʔarbaʕa/ |

| Five | خمسة | خَمْسَةٌ | khamsa | /xamsa/ |

| Six | ستة | سِتّةٌ | sitta | /sitːa/ |

| Seven | سبعة | سَبْعَةٌ | sabʿa | /sabʕa/ |

| Eight | ثمانية | ثَمَانِيَةٌ | thamāniya | /θamaːnija/ |

| Nine | تسعة | تِسْعَةٌ | tisʿa | /tisʕah/ |

| Ten | عشرة | عَشَرَةٌ | ashara | /ʕaʃarah/ |

| Eleven | أحد عشر | أَحَدَ عَشَرَ | ʾaḥada ʿashar | /ʔaħada ʕaʃar/ |

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Procházka, 2006.

- ↑ Wright, 2001, p. 492.

- ↑ "Arabic language." Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Retrieved on 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Versteegh, 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ "Arabic Language." Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009. Retrieved on 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Orville Boyd Jenkins (18 March 2000), Population Analysis of the Arabic Languages, http://strategyleader.org/articles/arabicpercent.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kaye, 1991.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Maltese language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9050379/Maltese-language. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Gregersen, 1977, p. 237.

- ↑ James Coffman (December 1995). "Does the Arabic Language Encourage Radical Islam?". Middle East Quarterly. http://www.meforum.org/article/276. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ↑ "Arabic - the mother of all languages - Al Islam Online". Alislam.org. http://www.alislam.org/topics/arabic/. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ <red name="Islam Q&A">Muhammad Saleh al-Munajjid (accessdate=2 August 2010). "هل اللغة العربية هي لغة أهل الجنة". islamqa.com. http://www.islamqa.com/ar/ref/83262.

- ↑ "A History of the Arabic Language". Linguistics.byu.edu. http://linguistics.byu.edu/classes/ling450ch/reports/arabic.html. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Kaplan and Baldauf, 2007, p. 48. See also Bateson, 2003, pp. 96–103 and Berber: Linguistic "Substratum" of North African Arabic by Ernest N. McCarus.

- ↑ MED Magazine

- ↑ Watson (2002:18)

- ↑ e.g. Thelwall (2003:52)

- ↑ Hetzron, 1997, p. 229.

- ↑ Hanna, 1972, p. 2

References

- Bateson, Mary Catherine (2003), Arabic Language Handbook, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 0878403868

- Gregersen, Edgar A. (1977), Language in Africa, CRC Press, ISBN 0677043805

- Grigore, George (2007), L'arabe parlé à Mardin. Monographie d'un parler arabe périphérique, Bucharest: Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti, ISBN 9789737372499, http://www.arc-news.com/read.php?lang=en&id_articol=1059

- Hanna, Sami A.; Greis, Naguib (1972), Writing Arabic: A Linguistic Approach, from Sounds to Script, Brill Archive, ISBN 9004035893

- Hetzron, Robert (1997), The Semitic languages (Illustrated ed.), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780415057677

- Haywood; Nahmad (1965), A new Arabic grammar, London: Lund Humphries, ISBN 085331585X

- Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. (2007), Language Planning and Policy in Africa, Multilingual Matters, ISBN 1853597260

- Kaye, Alan S. (1991), "The Hamzat al-Waṣl in Contemporary Modern Standard Arabic", Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 111 (3): 572–574, doi:10.2307/604273, http://www.jstor.org/stable/604273

- Lane, Edward William (1893), Arabic English Lexicon (2003 reprint ed.), New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 8120601076, http://www.studyquran.co.uk/LLhome.htm

- Mumisa, Michael (2003), Introducing Arabic, Goodword Books, ISBN 8178982110

- Procházka, S. (2006), ""Arabic"", Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.)

- Thelwall, Robin (2003), Arabic, "Handbook of the International Phonetic Association a guide to the use of the international phonetic alphabet", Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge), ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- Steingass, F. (1993), Arabic-English Dictionary, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 9788120608559, http://books.google.com/?id=3JXQh09i2JwC&dq=Arabic+English+thirsty

- Traini, R., Vocabolario di arabo, Rome: I.P.O.

- Versteegh, Kees (1997), The Arabic Language, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9004177027

- Vaglieri, Laura Veccia, Grammatica teorico-pratica della lingua araba, Rome: I.P.O.

- Watson, Janet (2002), The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198241372

- Wehr, Hans (1952), Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart: Arabisch-Deutsch (1985 reprint (English) ed.), Harassowitz, ISBN 3447019980

- Wright, John W. (2001), The New York Times Almanac 2002, Routledge, ISBN 1579583482

External links

- Google Ta3reeb – Arabic Keyboard using English/Latin Characters

- eiktub - Realtime Arabic transliteration

- Lane's Arabic-English Lexicon An 8-volume, 3000-page dictionary in PDF format.

- Arabic Language Books A Review of Arabic Language Books and Methods

- Arabic: a Category III language Languages which are exceptionally difficult for native English speakers

- Arabic grammar online

- Transliteration Arabic language pronunciation applet

- Dr. Habash's Introduction to Arabic Natural Language Processing

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||